by: Brian Davies, CFA – Chief Investment Officer

Printer friendly version here.

• The current trade situation between the U.S. and China resembles trade battles between the U.S. and Japan from the 1980’s.

• Japan then, like China today, was seen as a growing competitor to the U.S.’s economic standing in the world.

• Ultimately, in 1985 the trade tensions were somewhat defused by a multi-lateral agreement on currency called the Plaza Accord.

• In this article, we will examine the similarities between then and now and what it might mean for capital markets going forward.

In a 1991 ABC News-NHK survey, 60 percent of Americans said they viewed Japan’s economic strength as a threat to the United States.

In 1992, Senator Paul Tsongas, who was running for U.S. president at the time, said, “The Cold War is over, and Japan and Germany have won.”

In 1979 Ezra Vogel, a Harvard academic, wrote a book entitled Japan as Number One: Lessons for America in which he portrayed Japan, with its strong economy and cohesive society, as the world’s most dynamic industrial nation.

As the summer months heat up, the trade tensions between the U.S and China have followed suit. The Trump Administration has grown impatient with China and has threatened to put tariffs on the $300 billion worth of goods that are not currently taxed. Additionally, it has been threatened to go well beyond the 25% tariff level in place currently. China has responded by halting purchases on U.S. agriculture products. Currency has now entered the fray as the Yuan/Dollar exchange recently went above holy grail level of 7.0 for the first time. The Trump Administration has responded to this by calling China a currency manipulator. All of these developments have introduced a level of volatility into the equity markets that has many investors jittery. We feel like we have seen this movie before. We wanted to put some context to why the dispute today may be much like the dispute between the U.S. and Japan in the 1980’s. The text in the box above provides some context as to the U.S.’s sentiment in the 1980’s and 1990’s around Japan. As the saying goes, history does not repeat but, it often does rhyme.

In the 1970’s and 1980’s, Japan was a rising economy as it finally emerged from the catastrophe of World War II. Much like China today, they were seen as the great growth story of the time and people were euphoric to see what future held for them. As Chart 1 shows, Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in the 1980’s for Japan regularly grew at 5% per year or greater. This compares nicely with China’s growth rate over the past decade. China’s GDP growth for the last 10-years has ranged from as high as 12% and as low as 6%.

Chart 1

Japan GDP Annual Growth Rate:

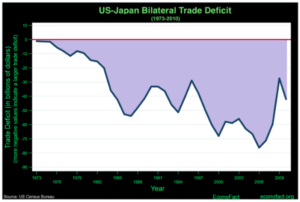

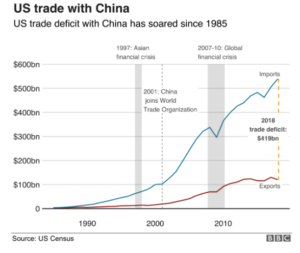

In the ‘70’s and ‘80’s, much of Japan’s growth was a result of booming trade. By 1985 the U.S. had a trade deficit with Japan (Chart 2) of around $53 billion or 1.2% of U.S. GDP. Compare that to the current day trade imbalance the U.S. has with China. The deficit to GDP measured just below 2.0% or $419 billion as of year-end 2018 (Chart 3). In both instances, U.S. officials wrung their hands and worried about what they perceived to be a burgeoning threat from a rapidly growing trade partner. The Reagan Administration used tariffs to influence trade in industries like semiconductors and steel. The Trump Administration has taken similar steps this go-around with China. They have gone so far as to threaten tariffs on all $500 billion of Chinese imports.

Chart 2

U.S.-Japan Trade Deficit 1973 to 2010:

Chart 3

U.S-China Trade Deficit 1985-2018

While tariffs were the first tool used to address the trade imbalance in the 1980’s, ultimately the dialogue switched to currency. The U.S. argued Japan was manipulating its currency (sound familiar?) and giving it an unfair advantage in trade. As Chart 4 shows, the Yen/Dollar exchange rate in the first half of the 1980’s saw the Dollar spike a couple of times; until 1985 that is. It was in 1985 that the U.S. struck a multilateral agreement. This agreement was called the Plaza Accord, with Britain, France, Germany and Japan to reduce the value of the Dollar. This did in fact work (chart 4) as the Yen rallied for the next three years. The U.S. trade deficit with Japan initially did decline but, as Chart 2 shows, it never turned into a trade surplus for the U.S.

You can see similar developments today as the U.S. is calling foul with China and its currency. As Chart 5 shows, the Dollar has maintained a relatively strong position to the Chinese Yuan over the last 5 years and again, it recently just peaked above seven Yuan/Dollar. Many people believe this move above seven is a result of the Chinese government letting the currency weaken to offset recently announced tariffs by the U.S. In the short-term the Yuan/Dollar has settled below 7.0. This is probably not the end of this story, but these movements have reverberated through the capital markets with a spike in volatility and has many in full blown risk off mode.

Chart 4

Yen/Dollar Exchange Rate: 1971-1995:

Chart 5

Yuan/Dollar Exchange Rate 2010 – Present

Summary: Our Positioning in Light of These Developments

Although we do not think the current trade spat will ultimately lead to the need for another currency agreement ala the Plaza Accord. We are fully aware that this trade situation between China and the U.S. is nowhere near being solved. As a result, volatility will be with us for a while. Coming into this summer, the global economy was slowing and this clearly is not helping. The global economy ex the U.S. has been in a growth recession for eighteen months now. While valuations outside the U.S are attractive, we are still waiting for better economic momentum to take a bigger position in those markets.

In the U.S., we came into the year knowing the economy was going to slow from the tax cut induced sugar high of 2018. So far, the economy seems to be following the pattern of slower growth with GDP seemingly running at just above 2.0% for 2019. This is not far off the U.S. economy’s long-run potential. We used the strong start to the year in U.S. equities to reduce our exposure to risk assets and allocate to more defensive securities. The massive move this summer into U.S. treasuries has surprised us and we think bond buyers might be a little ahead of themselves. While the trade dispute has slowed economic activity across the globe and in the U.S, we do not see it drawing the U.S. economy into a recession. The bond market rally seems to imply this to some extent. For us, the U.S. consumer (2/3 of the U.S. economy) is in really great shape, having spent this cycle deleveraging their personal balance sheets. Imbalances of past cycles (extremes in credit growth and valuations) do not seem to be in place this cycle yet. While we will never say never, it seems to us the combination of loose monetary policy, a stable U.S. consumer, and minimal imbalances should limit the downside for the U.S economy.

History has seen many, many trade disputes and sometimes we forget that we have been here before. We recognize all situations are different. We invest with a long-term perspective and a focus on risk adjusted returns. The capital markets will react to the news (tweets) as they see fit. We will be proactive and not reactive. We will look for dislocations as a result of spikes in volatility around developing trade news. When the pricing of risk gets pushed too far one way or the other, we will look to take advantage for our clients, all the while focused on long-term return potential. We hope you enjoyed this piece. Please reach out if you have any questions around the current trade situation or there are other concerns you wish to discuss.

DISCLOSURE:

The content in this material is for general information only and not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. All performance referenced is historical and is no guarantee of future results. All investing involves risk including loss of principal. No strategy assures success or protects against loss. The economic forecasts set forth in this material may not develop as predicted and there can be no guarantee that strategies promoted will be successful. International investing involves special risks such as currency fluctuation and political instability and may not be suitable for all investors. Government bonds and Treasury bills are guaranteed by the US government as to the timely payment of principal and interest and, if held to maturity, offer a fixed rate of return and fixed principal value. Bonds are subject to market and interest rate risk if sold prior to maturity. Bond values will decline as interest rates rise and bonds are subject to availability and change in price.